Fun facts to rekindle your interest in Silvermine Cave, the Shui Hau Mudflats and Fan Lau Fort and Stone Circle

PHOTOS BY Duey Tam

Fun facts to rekindle your interest in Silvermine Cave, the Shui Hau Mudflats and Fan Lau Fort and Stone Circle

PHOTOS BY Duey Tam

SILVERMINE CAVE

You’ll have heard, however vaguely, that Mui Wo was a centre for silver production in the late 19th century hence the name of its glorious bay, waterfall and ‘cave.’ In the late 1880s, at the height of the silver rush, people flocked to Mui Wo to work the mine, and the surrounding area was developed into a village called Pak Ngan Heung, literally translated as ‘Silver Village.’

The main entrance to the mine, now called Silvermine Cave, remains a local attraction. Today, the tunnel extends just 10 metres or so, having been sealed for safety reasons, but it reveals something of the large-scale silver mine, which was developed and owned by Ho A Mei, a local entrepreneur and social activist, and in operation from 1886 to 1896.

These days, with the miners long gone, Silvermine Cave has been taken over by a large colony of indigenous bats – Cynopterus Sphinx Short-nosed Fruit Bats to be precise. They’ve made their home in the dark, disused shafts and tunnels of the old mine, and their stay is secured by the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department.

The ‘bat cave’ sits just a few steps up the hill from Silvermine Waterfall, which is one of the prettiest and most easily accessible in Hong Kong. Walking up from Silvermine Bay, simply follow the path along the Islands Nature Heritage Trail – Mui Wo Section, and the Olympic Trail. It’s an easy 20-minute stroll through sleepy villages and there are no hills to climb.

SHUI HAU MUD FLATS

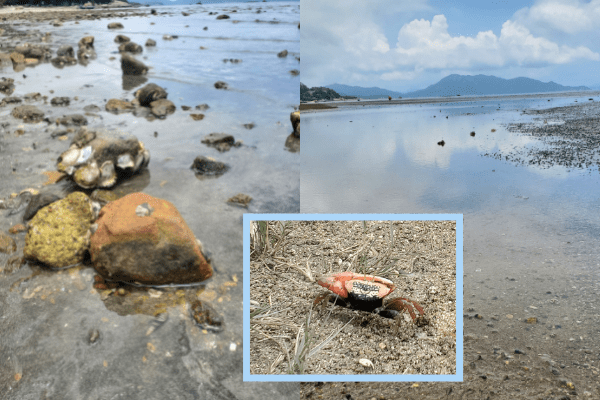

Situated in the far southwest of Lantau, Shui Hau is a designated marine reserve, and its mudflats are among the best coastal wetlands in Hong Kong.

The ecosystem in the mudflats is diverse with more than 180 species recorded. While beachcombing, you can expect to find giant Asiatic clams, spiral-shelled snails and cockles as big as your hand. Swarms of tiny fish ebb and flow in the nearby shallows attracting birds like the Little Egret and, during migration season, a few shorebirds.

Navigating your way across the mudflats at low tide, be prepared to witness hundreds of brightly coloured juvenile horseshoe crabs scurrying across the flat sandy beach, dipping in and out of their tiny holes in the sand.

Known as ‘Living fossils,’ juvenile horseshoe crabs spend an average of 10 years on the mudflats before migrating to the sea, when they reach sexual maturity. Shui Hau’s high biodiversity and soft flats ensure it is a suitable nursery – it is one of the few breeding sites in Hong Kong for this scarce and declining species.

The easiest way to get to Shui Hau is by bus from either Tung Chung or Mui Wo, and there are two routes to the mudflats. You can walk there from the village, past small vegetable plots and through abandoned fields. Or, you can take the equally tranquil path alongside a football pitch, just east of Shui Hau. Both paths lead to the west of Shui Hau Wan, where small streams run in from the hills.

FAN LAU FORT AND STONE CIRCLE

One of the best ways to get to Fan Lau is to hike there from the bus stop at Shek Pik; you’re headed for Lantau’s far southwestern tip, where there are no roads. The Qing dynasty fort and megalithic stone circle are a short way from the village. Walk along the beach towards the giant boulder on the far headland – and keep going.

You soon come across the fort, which was declared a monument in 1981. Built in 1729 to protect the Pearl River Estuary, it was occupied by pirate gangs later that century and then reconquered by Qing troops in 1810. The 10,500 square-foot, rectangular stone structure was manned by eight cannons and served as a garrison with 20 barracks. It was abandoned by the British around 1900.

Initial restoration work was undertaken on the fort in early 1985, followed by a large-scale restoration and repair project in 1990.

Fan Lau Stone Circle was declared a monument in 1983 – just don’t expect Stonehenge. It’s only 10 feet in diameter at its widest point and, if it were not for the fence around, it would be easy to miss. A few small stones form a circle on the ground, but a megalithic circle nonetheless. Dating somewhere between 5,000 and 2,000 BC, it was likely used for pagan rituals. An information plaque reveals that this kind of stone structure became common in China during the late Neolithic (New Stone Age) and early Bronze Age before spreading throughout the world.